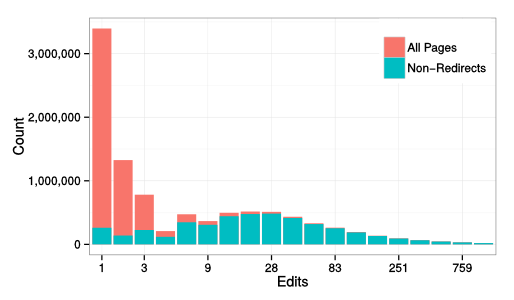

With more than 10 million users, the Scratch online community is the largest online community where kids learn to program. Since it was created, a central goal of the community has been to promote “remixing” — the reworking and recombination of existing creative artifacts. As the video above shows, remixing programming projects in the current web-based version of Scratch is as easy is as clicking on the “see inside” button in a project web-page, and then clicking on the “remix” button in the web-based code editor. Today, close to 30% of projects on Scratch are remixes.

Remixing plays such a central role in Scratch because its designers believed that remixing can play an important role in learning. After all, Scratch was designed first and foremost as a learning community with its roots in the Constructionist framework developed at MIT by Seymour Papert and his colleagues. The design of the Scratch online community was inspired by Papert’s vision of a learning community similar to Brazilian Samba schools (Henry Jenkins writes about his experience of Samba schools in the context of Papert’s vision here), and a comment Marvin Minsky made in 1984:

Adults worry a lot these days. Especially, they worry about how to make other people learn more about computers. They want to make us all “computer-literate.” Literacy means both reading and writing, but most books and courses about computers only tell you about writing programs. Worse, they only tell about commands and instructions and programming-language grammar rules. They hardly ever give examples. But real languages are more than words and grammar rules. There’s also literature – what people use the language for. No one ever learns a language from being told its grammar rules. We always start with stories about things that interest us.

In a new paper — titled “Remixing as a pathway to Computational Thinking” — that was recently published at the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Collaborative Work and Social Computing (CSCW) conference, we used a series of quantitative measures of online behavior to try to uncover evidence that might support the theory that remixing in Scratch is positively associated with learning.

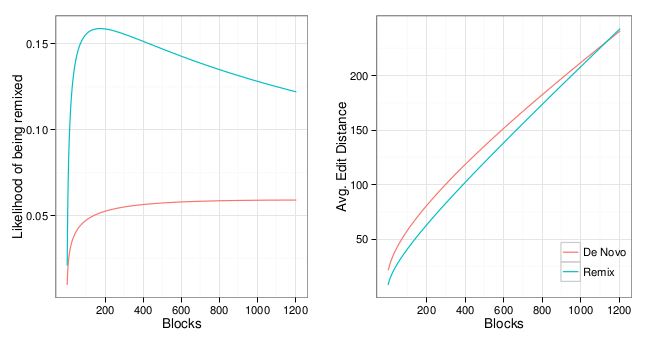

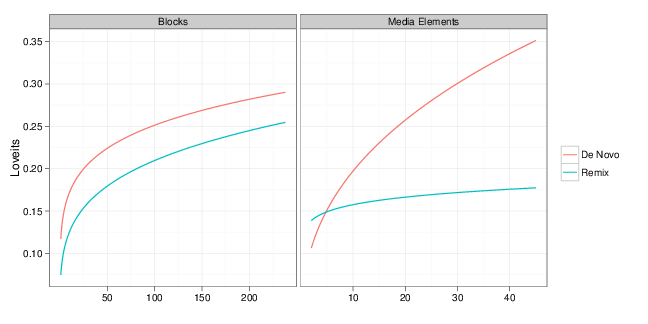

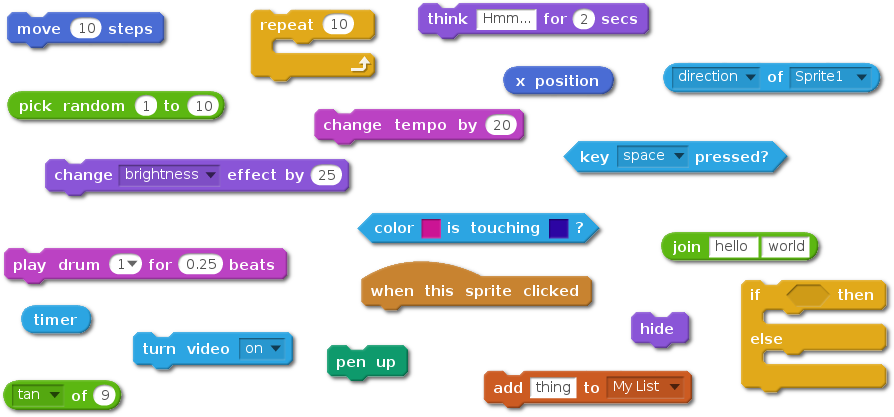

Of course, because Scratch is an informal environment with no set path for users, no lesson plan, and no quizzes, measuring learning is an open problem. In our study, we built on two different approaches to measure learning in Scratch. The first approach considers the number of distinct types of programming blocks available in Scratch that a user has used over her lifetime in Scratch (there are 120 in total) — something that can be thought of as a block repertoire or vocabulary. This measure has been used to model informal learning in Scratch in an earlier study. Using this approach, we hypothesized that users who remix more will have a faster rate of growth for their code vocabulary.

Of course, because Scratch is an informal environment with no set path for users, no lesson plan, and no quizzes, measuring learning is an open problem. In our study, we built on two different approaches to measure learning in Scratch. The first approach considers the number of distinct types of programming blocks available in Scratch that a user has used over her lifetime in Scratch (there are 120 in total) — something that can be thought of as a block repertoire or vocabulary. This measure has been used to model informal learning in Scratch in an earlier study. Using this approach, we hypothesized that users who remix more will have a faster rate of growth for their code vocabulary.

Controlling for a number of factors (e.g. age of user, the general level of activity) we found evidence of a small, but positive relationship between the number of remixes a user has shared and her block vocabulary as measured by the unique blocks she used in her non-remix projects. Intriguingly, we also found a strong association between the number of downloads by a user and her vocabulary growth. One interpretation is that this learning might also be associated with less active forms of appropriation, like the process of reading source code described by Minksy.

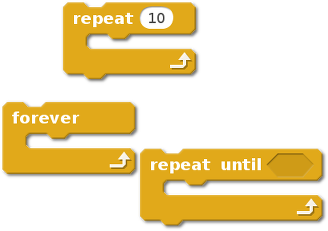

The second approach we used considered specific concepts in programming, such as loops, or event-handling. To measure this, we utilized a mapping of Scratch blocks to key programming concepts found in this paper by Karen Brennan and Mitchel Resnick. For example, in the image below are all the Scratch blocks mapped to the concept of “loop”.

We looked at six concepts in total (conditionals, data, events, loops, operators, and parallelism). In each case, we hypothesized that if someone has had never used a given concept before, they would be more likely to use that concept after encountering it while remixing an existing project.

We looked at six concepts in total (conditionals, data, events, loops, operators, and parallelism). In each case, we hypothesized that if someone has had never used a given concept before, they would be more likely to use that concept after encountering it while remixing an existing project.

Using this second approach, we found that users who had never used a concept were more likely to do so if they had been exposed to the concept through remixing. Although some concepts were more widely used than others, we found a positive relationship between concept use and exposure through remixing for each of the six concepts. We found that this relationship was true even if we ignored obvious examples of cutting and pasting of blocks of code. In all of these models, we found what we believe is evidence of learning through remixing.

Of course, there are many limitations in this work. What we found are all positive correlations — we do not know if these relationships are causal. Moreover, our measures do not really tell us whether someone has “understood” the usage of a given block or programming concept.However, even with these limitations, we are excited by the results of our work, and we plan to build on what we have. Our next steps include developing and utilizing better measures of learning, as well as looking at other methods of appropriation like viewing the source code of a project.

This blog post and the paper it describes are collaborative work with Sayamindu Dasgupta, Andrés Monroy-Hernández, and William Hale. The paper is released as open access so anyone can read the entire paper here. This blog post was also posted on Sayamindu Dasgupta’s blog and on Medium by the MIT Media Lab.