Leaders and scholars of online communities tend of think of community growth as the aggregate effect of inexperienced individuals arriving one-by-one. However, there is increasing evidence that growth in many online communities today involves newcomers arriving in groups with previous experience together in other communities. This difference has deep implications for how we think about the process of integrating newcomers. Instead of focusing only on individual socialization into the group culture, we must also understand how to manage mergers of existing groups with distinct cultures. Unfortunately, online community mergers have, to our knowledge, never been studied systematically.

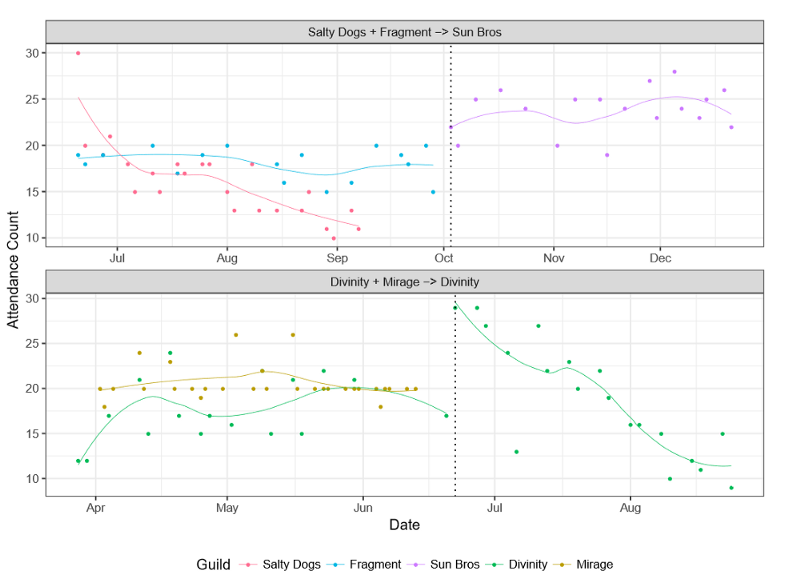

To better understand mergers, my student Charlie Kiene spent six months in 2017 conducting ethnographic participant observation in two World of Warcraft raid guilds planning and undergoing mergers. The results—visible in the attendance plot below—shows that the top merger led to a thriving and sustainable community while the bottom merger led to failure and the eventual dissolution of the group. Why did one merger succeed while the other failed? What can managers of other communities learn from these examples?

In a new paper that will be published in the Proceedings of of the ACM Conference on Computer-supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (CSCW) and that Charlie will present in New Jersey next month, I teamed up with Charlie and Aaron Shaw try to answer these questions.

In our research setting, World of Warcraft (WoW), players form organized groups called “guilds” to take on the game’s toughest bosses in virtual dungeons that are called “raids.” Raids can be extremely challenging, and they require a large number of players to be successful. Below is a video demonstrating the kind of communication and coordination needed to be successful as a raid team in WoW.

Because participation in a raid guild requires time, discipline, and emotional investment, raid guilds are constantly losing members and recruiting new ones to resupply their ranks. One common strategy for doing so is arranging formal mergers. Our study involved following two such groups as they completed mergers. To collect data for our study, Charlie joined both groups, attended and recorded all activities, took copious field notes, and spent hours interviewing leaders.

Although our team did not anticipate the divergent outcomes shown in the figure above when we began, we analyzed our data with an eye toward identifying themes that might point to reasons for the success of one merger and the failure of the other. The answers that emerged from our analysis suggest that the key differences that led one merger to be successful and the other to fail revolved around differences in the ways that the two mergers managed organizational culture. This basic insight is supported by a body of research about organizational culture in firms but seem to have not made it onto the radar of most members or scholars of online communities. My coauthors and I think more attention to the role that organizational culture plays in online communities is essential.

We found evidence of cultural incompatibility in both mergers and it seems likely that some degree of cultural clashes is inevitable in any merger. The most important result of our analysis are three observations we drew about specific things that the successful merger did to effectively manage organizational culture. Drawn from our analysis, these themes point to concrete things that other communities facing mergers—either formal or informal—can do.

First, when planning mergers, groups can strategically select other groups with similar organizational culture. The successful merger in our study involved a carefully planned process of advertising for a potential merger on forums, testing out group compatibility by participating in “trial” raid activities with potential guilds, and selecting the guild that most closely matched their own group’s culture. In our settings, this process helped prevent conflict from emerging and ensured that there was enough common ground to resolve it when it did.

Second, leaders can plan intentional opportunities to socialize members of the merged or acquired group. The leaders of the successful merger held community-wide social events in the game to help new members learn their community’s norms. They spelled out these norms in a visible list of rules. They even included the new members in both the brainstorming and voting process of changing the guild’s name to reflect that they were a single, new, cohesive unit. The leaders of the failed merger lacked any explicitly stated community rules, and opportunities for socializing the members of the new group were virtually absent. Newcomers from the merged group would only learn community norms when they broke one of the unstated social codes.

Third and finally, our study suggested that social activities can be used to cultivate solidarity between the two merged groups, leading to increased retention of new members. We found that the successful guild merger organized an additional night of activity that was socially-oriented. In doing so, they provided a setting where solidarity between new and existing members can cultivate and motivate their members to stick around and keep playing with each other—even when it gets frustrating.

Our results suggest that by preparing in advance, ensuring some degree of cultural compatibility, and providing opportunities to socialize newcomers and cultivate solidarity, the potential for conflict resulting from mergers can be mitigated. While mergers between firms often occur to make more money or consolidate resources, the experience of the failed merger in our study shows that mergers between online communities put their entire communities at stake. We hope our work can be used by leaders in online communities to successfully manage potential conflict resulting from merging or acquiring members of other groups in a wide range of settings.

Much more detail is available our paper which will be published open access and which is currently available as a preprint.

Both this blog post and the paper it is based on are collaborative work by Charles Kiene from the University of Washington, Aaron Shaw from Northwestern University, and Benjamin Mako Hill from the University of Washington. We are also thrilled to mention that the paper received a Best Paper Honorable Mention award at CSCW 2018!

2 Replies to “Why organizational culture matters for online groups”