In late July, the Awesome Foundations invited me to participate in an interesting conversation about open brands at their conference. Awesome is a young collection of organizations struggling with the idea of if, and how, they want to try to control who gets call themselves Awesome. I was asked to talk about how the free software community approaches the issue.

Guidance from free software is surprisingly unclear. I have watched and participated in struggles over issues of branding in every successful free software project I’ve worked in. Many years ago, Greg Pomerantz and I wrote a draft trademark policy for the Debian distribution over a couple beers. Over the last year, I’ve been working with Debian Project Leader Stefano Zacchiroli and lawyers at the Software Freedom Law Center to help draft a trademark policy for the Debian project.

Through that process, I’ve come up with three principles which I think lead to more clear discussion about whether a free culture or free software should register a trademark and, if they do, how they should think about licensing it. I’ve listed those principles below in order of importance.

1. We want people to use our brands. Conversation about trademarks seem to turn into an exercise in imagining all the horrible ways in which a brand might be misused. This is silly and wrong. It is worth being extremely clear on this point: Our problem is not that people will misuse our brands. Our problem is that not enough people will use them at all. The most important goal of a trademark policy should be to make legitimate use possible and easy.

We want people to make t-shirts with our logos. We want people to write books about our products. We want people to create user groups and hold conferences. We want people to use, talk about, and promote our projects both commercially and non-commercially.

Trademarks will limit the diffusion of our brand and, in that way, will hurt our projects. Sometimes, after carefully considering these drawbacks, we think the trade-off is worth making. And sometimes it is. However, projects are generally overly risk averse and, as a result, almost always err on the side of too much control. I am confident that free software and free culture projects’ desire to control their brands has done more damage than all brand misuse put together.

2. We want our projects to be able to evolve. The creation of a trademark puts legal power to control a brand in the hands of an individual, firm, or a non-profit. Although it might not seem like such a big deal, this power is, fundamentally, the ability to determine what a project is and is not. By doing this, it creates a single point of failure and a new position of authority and, in that process, limits projects’ ability to shift and grow organically over time.

I’ve heard that in US politics, there is no trademark for the terms Republican or Democrat and that you do not need permission to create an organization that claims to be part of either party. And that does not mean that everybody is confused. Through social and organizational structures, it is clear who is in, who is out, and who is on the fringes.

More importantly, this structure allows for new branches and groups outside of the orthodoxy to grow and develop on the margins. Both parties have been around since the nineteenth century, have swapped places on the political spectrum on a large number of issues, and have played host to major internal ideological disagreements. Almost any organization should aspire to such longevity, internal debate, and flexibility.

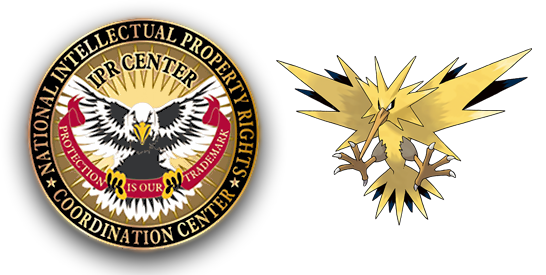

3. We should not confuse our communities. Although they are often abused, trademarks are fundamentally pro-consumer. The point of legally protected brands is to help consumers from being confused as the source of a product or service. Users might love software from the Debian project, or might hate it, but it’s nice for them to be able to know that they’re getting "Debian Quality" when they download a distribution.

Of course, legally protected trademarks aren’t the only way to ensure this. Domains names, internal policies, and laws against fraud and misrepresentation all serve this purpose as well. The Open Source Initiative applied for a trademark on the term open source and had their application rejected. The lack of a registered trademark has not kept folks from policing use of the term. Folks try to call their stuff "open source" when it is not and are kept in line by a community of folks who know better.

And since lawyers are rarely involved, it is hardly clear that a registered trademark would help in the vast majority of these these situations. It is also the case that most free software/culture organizations lack the money, lawyers, or time, to enforce trademarks in any case. Keeping your communities of users and developers clear on what is, and what isn’t, your product and your project is deeply important. But how we choose to do this is something we should never take for granted.