About a year ago, I was working on OLPC during most of the time and thinking a lot about software freedom in the context of the project. My blog post on OLPC and Charges of Technological and Cultural Imperialism from last December is a great example of my thinking out loud about some of the issues.

The attractive thing to me about OLPC was the idea of students getting a real, free software, free hardware, truly open platform unlike phones, calculators, and eBooks: closed paternalist platforms that seem to be the only real alternatives. This is a goal that OLPC has not achieved yet but has already come quite close to.

People say that because modifying technology is often difficult, only a small percentage of users — especially young users — will take advantage of the malleability or "hackability" of a product. They are probably right. But part of why this happens is because when computers are employed in education, we use them as tools to accomplish predefined and preprogrammed tasks. Even when students learn to program, it’s in a window (quite literally in a box) separate from the rest of the things that the computer does.

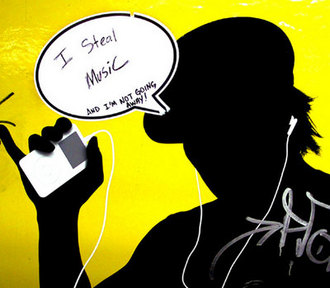

And for someone working on a project in part so that they can spread technological freedom, this is a problem. Consider the fact that with only a small number of exceptions, the only advocates of software freedom I know are programmers or hackers. I don’t think that this is because of some "programmer’s sensibility" but rather because programmers understand a set of things about the malleability of software and the nature, effect, and context of computation that gives them perspective to understand how a concept like freedom might apply to something like software. In other words, to understand software freedom, you must first understand — really understand — what software is and what it is not, how it makes things possible and impossible, and how changing it can have important effects.

The mentality I’ve described is currently a "hacker’s sensibility" but I don’t believe that you need to be a hacker to understand why software freedom is important. Proof, I think, is the fact that people think that a free press is important even if they don’t publish or write very well.

As an exercise, I took it on myself to write the beginning of a curriculum that teachers could use to teach students about software freedom and the concepts that I think are key to understanding it. It tries to come up with models for framing discussions and a series of activities to help teachers teach relatively young (i.e., middle school students) about issues of computation, information goods, and ultimately about software freedom.

I wrote the curriculum about a year ago, showed it to a few teachers and colleagues, and then sat on it because I wasn’t sure what to do with it and because I was concerned by my own lack of experience teaching outside of Universities. I’m still not entirely sure about incredibly basic things like what form a curriculum should take for this age group.

I noticed recently that Wikiversity launched in August and it seems like the perfect place to put my curriculum for consumption by the world and for collaboration, discussion, and further development. You can see what I’ve got from this page and the pages linked from it:

http://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Software_Freedom

The project still needs lots of work. It needs to be threshed out on its own terms and it needs to be broken down and integrated into Wikiversity as a series of learning projects, learning activities, etc. I’ve looked at the documentation around Wikiversity and I can neither understand how to do this nor find examples of large curricula in Wikiversity to which this has already been done. If you have experience on Wikiversity, your help would be welcome.

If you are interested in using part of the curriculum, I would love to hear from you and to see your edits on the wiki.