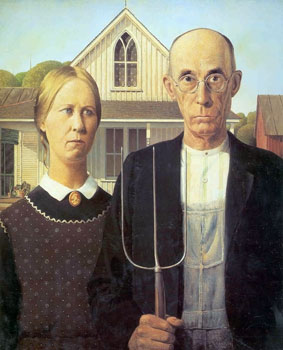

About a year ago, I read American Gothic by Steven Biel and the book has left a surprising lasting impression on me. The book describes the background, history, and life of "American Gothic: America’s most famous painting" by Grant Wood. Even if you don’t recognize the name "American Gothic", you are likely to recognize the picture or the scene. The book is a serious and — as far as I can tell — reasonably comprehensive treatment of the subject that is interesting, insightful at points, and a breeze to read.

Of course, the book is not actually about the painting that hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago — although it will certainly teach you more than you probably ever wanted to know about that painting, its subjects, its settings, etc. The book is really the story of how that paining has been received, understood, and used. Nearly half of the book focuses on examples of people who have remixed, reworked, reimagined, and reproduced the painting in myriad forms, formats, settings, and ways. The book contains scores of photographs of celebrities posing in American Gothic style settings, dozens of political cartoons based on the paintings, images of talk shows, magazine covers, Broadway plays, product advertisements, toys, gifts, kitch, and more, done up in recognizeable representations of the basic American Gothic form. There is a very incomplete of references to American Gothic in popular culture at Wikipedia that can give a tiny taste of what is out there.

The last chapter of the book is devoted to these "parodies" and there’s some brief talk of issues around copyright and control of the image. Wood’s sister Nan was the owner of the copyright for much of the second half of the twentieth century and is also the woman in the painting. She famously charged several makers of more lurid take-offs with defamation and successfully blocked a number of remixes. In 1988, Nan transferred ownership to the Visual Artists and Galleries Association (VAGA) which will hold the copyright until 2025. VAGA also claims "rights of publicity" in Nan’s image which will last until 2060. VAGA takes a very expansive view of its copyright claims and argues that it has both veto power and royalty rights to any recognizably similar work. For example, VAGA does not want the American Gothic image used in alcohol advertisements and has successfully had such ads pulled. Biel’s book contains no reference to the amount of money made from licensing the work but one can only conclude that it must be massive. VAGA blocked a plan by Iowa to use the picture on the back of the Iowa state quarter due to licensing disagreements; instead Iowa used a different Wood painting that was clearly in the public domain.

What struck me most about Biel’s book is related to just how deeply ingrained in American culture the American Gothic image has become. The book cites simple surveys that show that almost every American recognizes the painting (although only a small fraction know the painting’s name or who painted it). The thousands of parodies that the book documents are testament to the fact that the painting has become a way of representing something essential about American culture and its values. But in a strange way, the painting’s popularity and incessant reuse has also made it part of the culture that it so effectively captured.

We can think of culture as a set of shared values and references that help us related to each other and to communicate. Just like idioms in language, culture helps us communicate more effectively, certainly, but also lets us communicate messages that would not be communicable otherwise. When Out Magazine, Coors, or any of several dozen others replace the figures in American Gothic with a gay or lesbian couple, they are succinctly sending a message about homosexual relationships and American traditional values that could not be made any other way. In this way, American Gothic — both the painting and Biel’s book — represent a strong argument for free culture.

If American Society has infused American Gothic with so much value, how can it be fair to let one person or organization own it? Are they not owning an essential mode through which a society can relate, experience, and communicate? I can’t help but conclude that it shouldn’t matter if VAGA does not like alcohol, advertisements, homosexuality, or wants to make a some money every time someone makes a cartoon parody. These are trivial concerns next to the importance of our society’s need to communicate about these issues. If doing so requires the use of a shared cultural reference in VAGA’s painting, I find it hard to justify VAGA’s position of control.

We need to be able to reproduce and reimagine American Gothic because it has become part of us. It’s a striking example of the way that art becomes culture and the reason that truly free culture is the only appropriate response. We can’t afford to let our experience of the world and each other — to let ourselves at a very fundamental level — be owned and controlled.

One of my senior recital posters was an alteration of this image with the man holding a bassoon instead…

I’ve no objection to an artist having control over there work – look at Bill Waterson’s struggle to prevent Calvin & Hobbes being devalued by being slapped all over lunch boxes.

I certainly don’t object to their holding rights to make money, there’s a lot of art that I appreciate and am glad they took the time to make.

What I cannot understand is how an entity such as a corporation can buy those rights and hold the work to ransome over it. Did VAGA create it? Did they assist Wood financially while he was creating it? Are they using their rights to promote its access and preservation? If the answer to any of these is no then why are third parties allowed to buy copyright?

@Dougie, VAGA does not “own” the copyright. They represent visual artists and artists’ estates in the same way that BMI and ASCAP represent musicians. VAGA is not against “free culture” in terms of allowing more people access to art works through digital initiatives, as this article suggests : http://www.artstor.org/news/n-html/an-070809-vaga.shtml

What VAGA is for is the fair payment of royalties to artists and to their Estates. This is only fair, since people have to eat, pay their bills and what have you. “Free culture” should never mean taking their livelihood away from artists and their families. If someone creates a cultural icon, it is only fair that they and their estates should profit from it.

If you want to use the image, then ask the rights holder. If your request is valid, they will usually say “yes”, with reasonable compensation (or for free, if it is for educational purposes).

If you have a real problem with this, feel free to make your own cultural icon and make it free for everybody to use.

Benjamin, imagine you build a beautiful 4-bedroom house on a hill. It is unique, innovative, absolutely stunning. When you pass away, you bequeath the home to your daughter, her husband, and their child. They’ll essentially be using only two of the four bedrooms.

I and others have decided that this home is infused with so much value, how can it be fair to let one person or one family own it? They aren’t even using all of the bedrooms! Since the image of this home on a hill has become a part of me, I am going to move into the third bedroom, and I suggest that tourists be allowed to use the fourth bedroom on a per-night basis.

I hope your daughter and her family realize that truly free culture is the only appropriate remedy for their home. Oh, and stop spinning in your grave.

I’m all for creating scenarios to help explain controversial topics but seriously? This was one stupid irrelevant analogy.

Next?

Gregory, imagine that people could make perfect copies of that house at no cost to me or my relatives. That’s not exactly the same situation as the one you described, is it?

I’m not suggesting that artists not be compensated for their work. I am suggesting that culture is different than property in fundamental ways. If you use my house, I no longer have it. If you use the image in my painting, I do. Until we can distinguish between this, we will be thinking fuzzily about these issues.

If folks critique american culture using this painting (as opposed to making a simple copy), can VAGA take away their fair use defense? I assume not, but of course that requires resources that most artists lack.

@Paul – why should the families and estates of an artist benefit from their works for the rest of time?

If you had read my post then you would have noted how I clearly stated that Artists should be able to make money from their work and be able to defend how it is used.

I simply don’t see why this should extend to their descendants and absolutely don’t see why this is their “right”.

Thanks for posting this. I might use part of the book if I ever get around to teaching an IP class.